Today TDN launches the first installment in a multi-part series highlighting racetrack photographers. We'll be profiling the unique relationships between cameras and Thoroughbreds, asking about the most memorable horses, races and people they've viewed through the lens, and talking about how the craft of equine imagery has evolved. Each time that we profile a photographer, TDN will also be featuring their hand-selected favorite shots in multiple editions throughout the week.

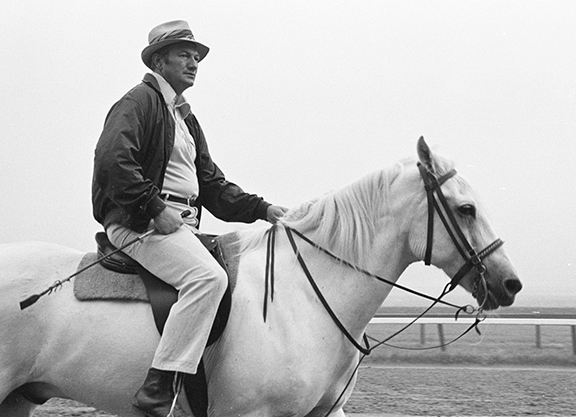

First up is Harold Roth. A 1973 racetrack photojournalism assignment for his Queens College student newspaper led to Roth's eventual founding of Horsephotos, the world's preeminent equine photo library. More than four decades later, Roth and his longtime team of 20 or so photographers have compiled more than four million digital images of Thoroughbreds, major races, the Eclipse Awards, sales and the backstretch.

After developing a taste for racing with that first photo shoot, Roth freelanced for Turf and Sport Digest during the Secretariat era while pursuing work as a commercial photographer. One of his early ad agency assignments involved Belmont Park, which dovetailed into his getting hired by the New York Racing Association (NYRA) to shoot everything from billboards to program covers through the early 1980s. Along the way, Roth separately helped create images for 30 children's books, including Harold Roth's Big Book of Horses.

In the mid-1980s, Roth got the idea to create the horse industry's first stock photo agency. In 1995, Roth rebranded the company as Horsephotos. The California-based firm's clients include international media outlets like TDN, the National Thoroughbred Racing Association and TVG. In addition, Horsephotos is routinely called upon for special assignments, like providing still shots for the films Seabiscuit and Dreamer. An edited transcript of a recent phone interview with Roth follows.

TDN: You have a reputation as an old-school photographer in terms of fundamentals, but it's well known you don't exactly pine for the “good old days” of film and darkrooms. Is that a fair description?

HR: I think you hit that pretty close to being on the head. Although I liked darkrooms, it was slow, tedious and not as rewarding as the digital format. As soon as the digital format presented itself shooting-wise, editing-wise and retouching-wise, it was just perfect for what I thought I needed to be doing moving forward. And the viewer is probably the greatest authority [of which format delivers better results].

TDN: Beyond the 21st Century transition to digital photography, what was another game-changing breakthrough during your time behind the camera?

HR: The changing of the technology from manual focus to auto-focus, and from manual advancing of the film one frame at a time to automatic, rapid advancing, were very big in the 1970s. In the 1971 Belmont S., Canonero II was going for the Triple Crown and Pass Catcher beat him. But the jockey of Pass Catcher dropped his whip and somebody got a shot. That was an award-winning photo. He was only able to get that by either getting lucky or by being able to advance the camera rapidly enough to take multiple shots. If you don't have to manage the technology because the technology manages itself due to the automation, that is an advancement that I am all for. The craft has nothing to do with technology. Real craft has to do with vision.

TDN: You're a minimalist. Tell us about your preferred setup.

HR: I enjoy using my cell phone more than anything. You don't have to carry anything else with you. Here's a quick story how I gravitated more to a point-and-shoot camera as opposed to the Nikon F2 that I was using: My wife was working as publicity director at Random House in New York City, and she would invite me to photograph book launch parties. And about every other party, a fellow named Andy Warhol would appear. I would take my large F2 with a potato-masher flash on it and I would point it at him. One day he came up to me and said, “You know, I see you around, and I want you to consider this Canon Sure Shot that I have because people will be less affected by that than this big thing coming in their face.” From then o,n I started shooting everything with [a small-format] Olympus XA camera. I even shot boxing matches ringside with that. It was just the most brilliant mental segue–from a being a wannabe photographer to being somebody that doesn't get in your face. And Andy Warhol was the one who set me straight.

TDN: How did your years shooting ads for NYRA affect your style?

HR: [Ad designers] never wanted a standard shot. “Shoot it from an angle that I haven't seen,” was their mandate for billboards and posters. If you came to them with a standard shot, they would beat you up. Advertising people have a whole different breed of consciousness. They're keyed up a little higher than editorial people. So for the first 20 years I didn't shoot as much editorial.

TDN: Today with Horsephotos, how much of your energy goes into managing the business versus actually getting out to shoot horses?

HR: Managing would be in the 90%-plus range, and shooting horses would be 5% or less. Generally, when I go to the racetrack with my photographers, I will be in charge of designating and directing camera locations and equipment, and also editing their shots. Basically, I'm relieving them of everything other than making things look as good as they can from their position.

TDN: Do you miss the shooting aspect or do those directive challenges satisfy your creative appetite?

HR: When I was shooting, I was only able to be in one location. If the action occurred where you were, you got lucky. Now I'm able to designate multiple people at multiple locations and realize a vision for multiple places. When they bring back their digital files for me to edit, I will always ask, “What happened in your position that I need to look at really carefully?” I'm in a more exciting position. I'm very lucky to be in a position like this. Other people might have the anxiety of wanting to be in a different part of the action. They don't know the value or enjoyment of this action.

TDN: Last week was supposed to be GI Kentucky Derby week, but it's been postponed because of the pandemic. How would you have deployed your Horsephotos team to shoot Derby Day?

HR: Derbies are pretty much a standard procedure. We try to get six to eight players. We will have a person shooting two finishes from the finish line; one would be with a 200 mm lens, and one with a 300 mm. We would shoot a head-on with a 600 or 800 mm. We would put down two cameras under the rail shooting the winner with the spires in the background, and one of them head-on. We would have a person on the inside [rail] on a ladder, and we would have someone on the turn and also on the roof. After the race, we would have two people shooting the winner's circle. Derby Days we have to keep everybody calm and focused on what they're supposed to be doing.

TDN: Beyond action shots, you also photograph backstretch scenes. What stands out for you when shooting there?

HR: Light. I will go to a barn where the shot that I want is conducive to light. If a horse is being bathed, and I were able to get backlight that radiates behind the horse and lets the “smoke” come off of a horse's body going up in the air, I would look for that. Since most horses look the same and most barns follow similar routines, you have to figure out how to make it unique. And the only thing that can do that is the light.

TDN: For fun, what other subjects do you like to shoot?

HR: Everything in this world! I just finished a multimedia project called “Billboards.” I've been shooting them for 30 or 40 years. I do street lights. I do street signs, murals and buildings. I do food trucks. I do diners, clouds, flowers and any pop art that I can. I do cars, airplanes and boats, and I like to find unique ones. I recently found a 1954 Hudson in somebody's front yard. The day before we photographed a purple McLaren, which we found out the guy paid $270,000 for. But it's so purple! I mean, you would not believe how purple-y it is! And I take a lot of pictures of my family and my grandchild.

Not a subscriber? Click here to sign up for the daily PDF or alerts.